Liza J. Rankow’s “Soul Medicine for a Fractured World” – Review by Felicia Murrell

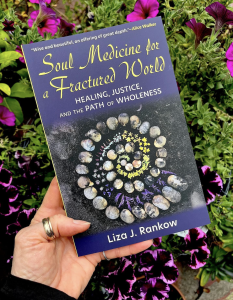

Soul Medicine for a Fractured World: Healing, Justice, and the Path of Wholeness

by Dr. Liza J. Rankow

Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2026

225 pages, USD$26.00

Reviewed by Felicia Murrell

In an era defined by profound global disorientation, Dr. Liza J. Rankow’s Soul Medicine for a Fractured World: Healing, Justice, and the Path of Wholeness emerges as a vital salve and a revolutionary call to action. This text is more than a book; it is a profound exploration of how we might guide ourselves through the enormous atrocities of our time by grounding our work in the context of eternality and the cosmos.

At the core of our vocation is the practice of presence, and Rankow’s work serves as a true masterclass in deep listening. She defines this not merely as an auditory skill, but as a holistic practice of listening with our whole being to open ourselves to Spirit. Rankow’s insights provide a robust framework for helping us sit with the sediment that lies in the recesses of our individual and collective soul. She reframes this disruption not as a cruelty, but as a grace—a divine invitation to alignment.

One of the most valuable contributions of this manuscript is its ability to shift the seeker’s perspective from the overwhelmed little me to a self situated within a larger, sacred body. Rankow reminds us that we are part of an unbroken chain rooted in Love, encompassing ancestors, future generations, and all of nature. This expansive inclusivity is essential for navigating crisis and upheaval. Her work invites us to move beyond the paralyzing chaos of the present moment and find strength in the Infinite.

Central to this shift is a fundamental inquiry that strikes at the heart of the contemplative life: What is it to know ourselves as part of one another and kin to all life? How does that knowing shift your own ideas about responsibility and the life we are building together—a life where all belong and all contribute to one another from a place of deep care and intentionality?

Focusing on the intersection of spirituality and social justice, Rankow provides a clear pathway. She challenges us to move toward “a whole-souled commitment” to be “aligned within ourselves, at our innermost core and with all that we are”—a state of embodied integrity that honors the sacred wholeness of Life. This book encourages a “disciplined soul force” (120) where love becomes more than a reactive emotion; it becomes the engine for social responsibility. Rankow asks: “Where are we contributing to the very conditions we deplore—violence, poverty, injustice, environmental destruction (117)?”

Inviting us to confront difficult truths, even within ourselves, Rankow empowers us to become active agents of transformation and repair, helping to “hospice the dying world, while simultaneously midwifing the emerging one (6).”

Soul Medicine for a Fractured World is an essential companion for anyone seeking to connect more deeply and find strength beyond the noise of the modern world. Dr. Rankow offers a wisdom that invites us to move beyond the need for certainty and instead live comfortably in mystery. Whether used for personal enrichment or as a foundational text in training programs, this work is a profound reminder that we are resourced by the Infinite to respond to our historical moment with transformative love.

Felicia Murrell is a spiritual director and the author of AND: The Restorative Power of Love In An Either/Or World, with over 20 years of church leadership experience and certifications as a Master Life Coach and Enneagram Practitioner. For more about Felicia, visit her website: www.feliciamurrell.com

Soul Medicine for a Fractured World: Healing, Justice, and the Path of Wholeness

by Dr. Liza J. Rankow

Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2026

225 pages, USD$26.00

Reviewed by Felicia Murrell

In an era defined by profound global disorientation, Dr. Liza J. Rankow’s Soul Medicine for a Fractured World: Healing, Justice, and the Path of Wholeness emerges as a vital salve and a revolutionary call to action. This text is more than a book; it is a profound exploration of how we might guide ourselves through the enormous atrocities of our time by grounding our work in the context of eternality and the cosmos.

At the core of our vocation is the practice of presence, and Rankow’s work serves as a true masterclass in deep listening. She defines this not merely as an auditory skill, but as a holistic practice of listening with our whole being to open ourselves to Spirit. Rankow’s insights provide a robust framework for helping us sit with the sediment that lies in the recesses of our individual and collective soul. She reframes this disruption not as a cruelty, but as a grace—a divine invitation to alignment.

One of the most valuable contributions of this manuscript is its ability to shift the seeker’s perspective from the overwhelmed little me to a self situated within a larger, sacred body. Rankow reminds us that we are part of an unbroken chain rooted in Love, encompassing ancestors, future generations, and all of nature. This expansive inclusivity is essential for navigating crisis and upheaval. Her work invites us to move beyond the paralyzing chaos of the present moment and find strength in the Infinite.

Central to this shift is a fundamental inquiry that strikes at the heart of the contemplative life: What is it to know ourselves as part of one another and kin to all life? How does that knowing shift your own ideas about responsibility and the life we are building together—a life where all belong and all contribute to one another from a place of deep care and intentionality?

Focusing on the intersection of spirituality and social justice, Rankow provides a clear pathway. She challenges us to move toward “a whole-souled commitment” to be “aligned within ourselves, at our innermost core and with all that we are”—a state of embodied integrity that honors the sacred wholeness of Life. This book encourages a “disciplined soul force” (120) where love becomes more than a reactive emotion; it becomes the engine for social responsibility. Rankow asks: “Where are we contributing to the very conditions we deplore—violence, poverty, injustice, environmental destruction (117)?”

Inviting us to confront difficult truths, even within ourselves, Rankow empowers us to become active agents of transformation and repair, helping to “hospice the dying world, while simultaneously midwifing the emerging one (6).”

Soul Medicine for a Fractured World is an essential companion for anyone seeking to connect more deeply and find strength beyond the noise of the modern world. Dr. Rankow offers a wisdom that invites us to move beyond the need for certainty and instead live comfortably in mystery. Whether used for personal enrichment or as a foundational text in training programs, this work is a profound reminder that we are resourced by the Infinite to respond to our historical moment with transformative love.

Felicia Murrell is a spiritual director and the author of AND: The Restorative Power of Love In An Either/Or World, with over 20 years of church leadership experience and certifications as a Master Life Coach and Enneagram Practitioner. For more about Felicia, visit her website: www.feliciamurrell.com Plough’s “Bread & Wine: Readings for Lent & Easter” – Review by Bradley Jersak

Plough Publishing has once again offered a high-quality treasure-trove from Christianity’s classical authors. Bread & Wine: Readings for Lent & Easter is a beautiful hardcover (with sleeve) expanded edition of daily devotional readings for Lent and Easter.

The Threshold of Joy – Eric H Janzen

The Threshold of Joy It was night, but they dared not sleep In the starlit darkness, they watched The wind caught the sound of their sheep Resting as though the world were at peace These soul-weary shepherds all wondered Would the blind ever see once more? Would the...

Resurrection and Restoration: Julian of Norwich & the Apostle Paul on Divine Love’s Ultimate Triumph by Eunike Jonathan

Julian’s vision parallels that of the Apostle Paul, whose writings proclaim the same mystery of grace and the ultimate reconciliation of all creation in Christ. For both, revelation is not private possession but charism—a gift freely given for the building up of the Church.3 Though separated by fourteen centuries, both bear witness to the same mystery of divine love revealed in the resurrection4—the reconciliation of all creation in Christ (1 Cor. 15).

Is Toryism Dead in Canada? Ron Dart

Ron Dart: Is Toryism Dead in Canada? The Red Tory Element in Canadian Conservatism

The Beatitudes Revisioned with Glasses Borrowed from Ron Dart – Tara Boothby

The Beatitudes Revisioned with Glasses Borrowed from Ron Dart in Honour of His 75th Birthday by Tara Boothby To Ron on your 75 th Birthday. You are loved. You have planted legacy in my life and in the lives of so many that I hold dear. Thank you, dear teach. Thank...

Clarion Site Update

Greetings, friends of Clarion Journal, At the end of September, Typepad, the internet platform that has housed the Clarion Journal for the past 20+ years, informed us that they are shutting down. They gave us a one-click export option to save our files for transport...

Embodied Integrity Through Beauty and Resistance – Jonathan Walton

Embodied Integrity Through Beauty and Resistance Adapted from Beauty and Resistance by Jonathan Walton In 2 Corinthians 5, we learn that we are Christ’s ambassadors and have been given the ministry of reconciliation. In Acts 1 we read that we will be his witnesses. It...

A More Merciful Beginning: Jesus’ and the Qur’an’s Shared Response to the Fall – Safi Kaskas

A More Merciful Beginning: Jesus' and the Qur'an's Shared Response to the Fall By: Safi Kaskas Introduction: A History Begging for Mercy For centuries, the story of humanity’s beginning has been told as a tragedy. In Western Christian theology, the...

A More Merciful Beginning: the Qur’anic Response to the Fall – by Safi Kaskas

Adamo id Eva - 1790 Editor's Note: In the spirit of multi-faith friendship and collaboration, we share Safi Kaskas's paper on "A More Merciful Beginning: The Qur'anic Response to the Fall," which highlights key aspects of how the Qur'an...

Lauren Southern’s “This is Not Real Life” – Review by Luke Schulz

The Private Implosion and Quest for Redemption of a Notorious Public Figure Lauren Southern’s This is not Real Life – A Memoir in Review Review by Luke Schulz Full disclosure: I know Lauren Southern personally. We have never been close, but back...